Annie’s story

It was a summer day at Sydney’s Bondi Beach, and the place was buzzing. Annie*, 21, and a friend had just got out of the water. Towels wrapped around their waists, they decided to walk to the promenade to have lunch.

“Hey, honeys! Need a ride home?” two men shouted from a passing car.

Annie and her friend felt shocked and humiliated. To make matters worse, she recalls, “there were so many people around and no one said anything. One person looked at them, looked at us, and then smiled and kept walking.”

Reflecting on the incident, she adds:

“We can’t even go to the beach and have a relaxing day. We felt so dirty.”

Later on, as the pair were waiting at a bus stop, a ute drove past, and the men inside clucked at the women like chickens. Then they halted at a red light.

“They just kept at it and we ignored it as best as we could,” says Annie.

“It bothered me so much, though, because when they left, I wished I had retaliated, or that someone had said something.

“I always wonder how the situation may have been different. Would it have stopped them from doing it again?”

What is street harassment?

One dictionary definition of street harassment is “unwelcome comments or contact of a sexual nature directed at a person by a stranger in a public place”. It can include honking a car horn, catcalling, wolf-whistling, making lewd gestures, and shouting out sexually suggestive comments.

When challenged, perpetrators of street harassment often claim they were merely paying a compliment. But those subjected to it don’t feel that way. They feel embarrassed, “dirty”, threatened.

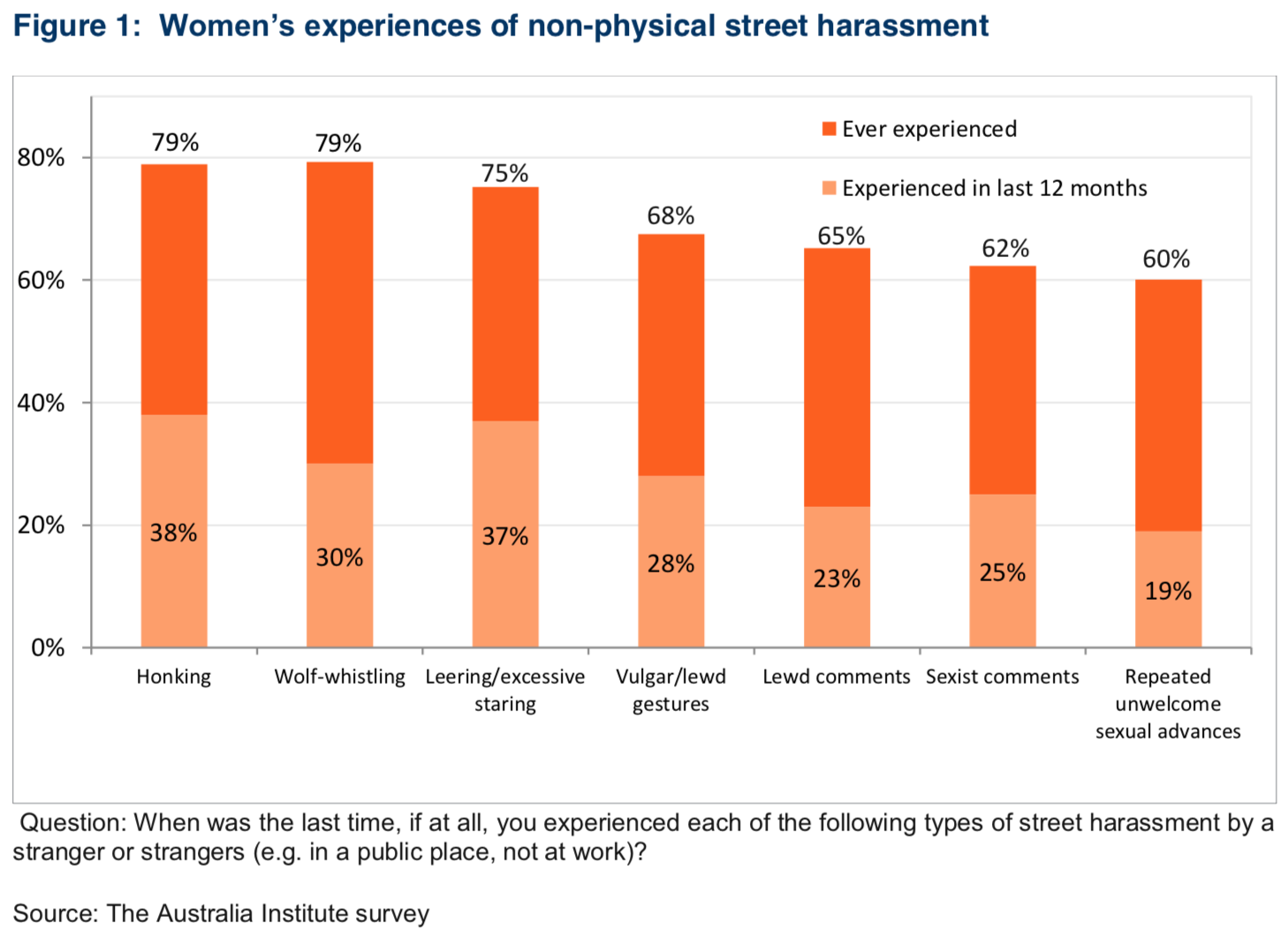

According to a survey by the Australia Institute in 2015, 79 per cent of women have experienced honking and wolf-whistling. Nearly two-thirds have been on the receiving end of lewd or sexist comments, and 60 per cent have had repeated unwelcome sexual attention.

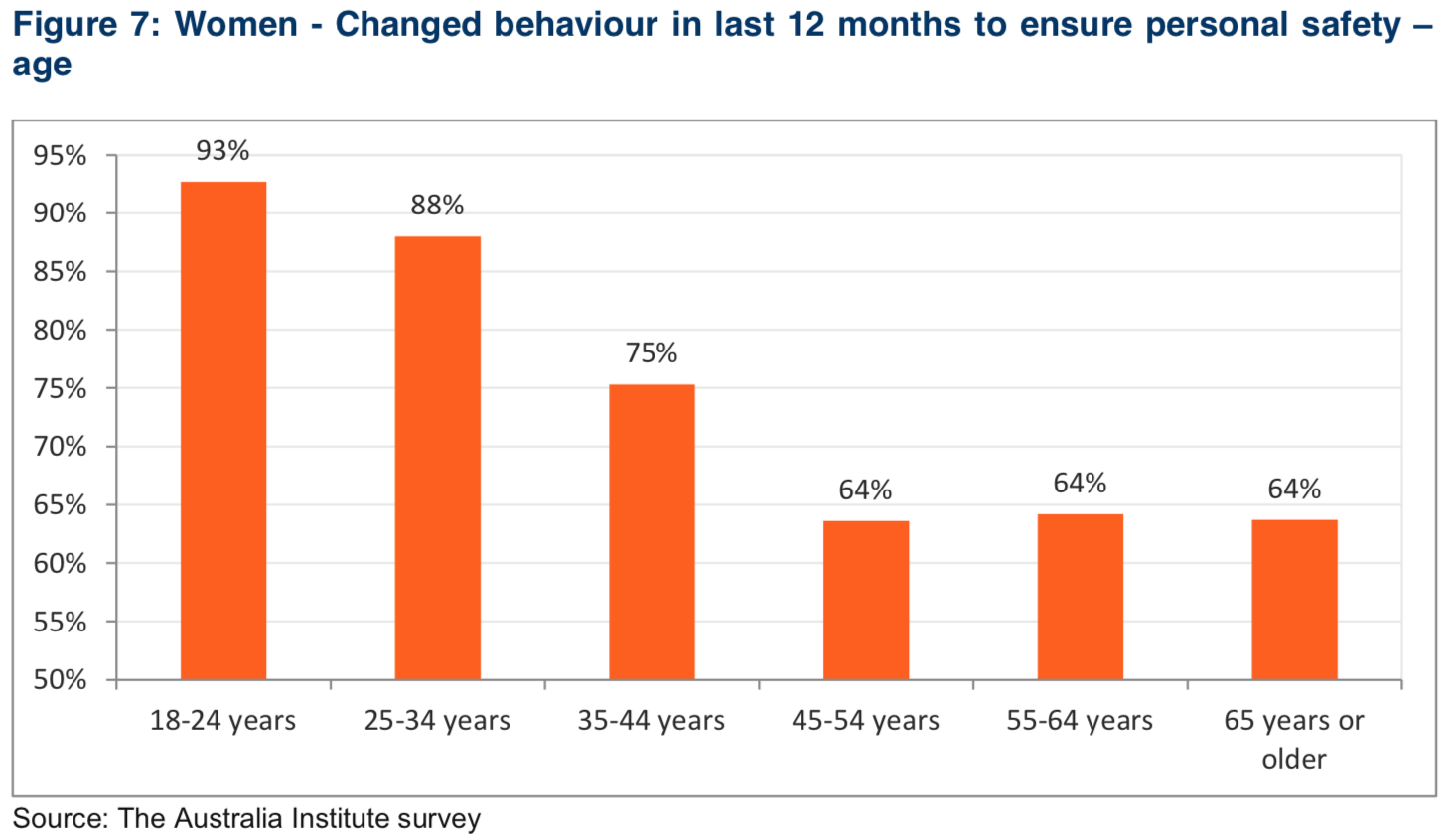

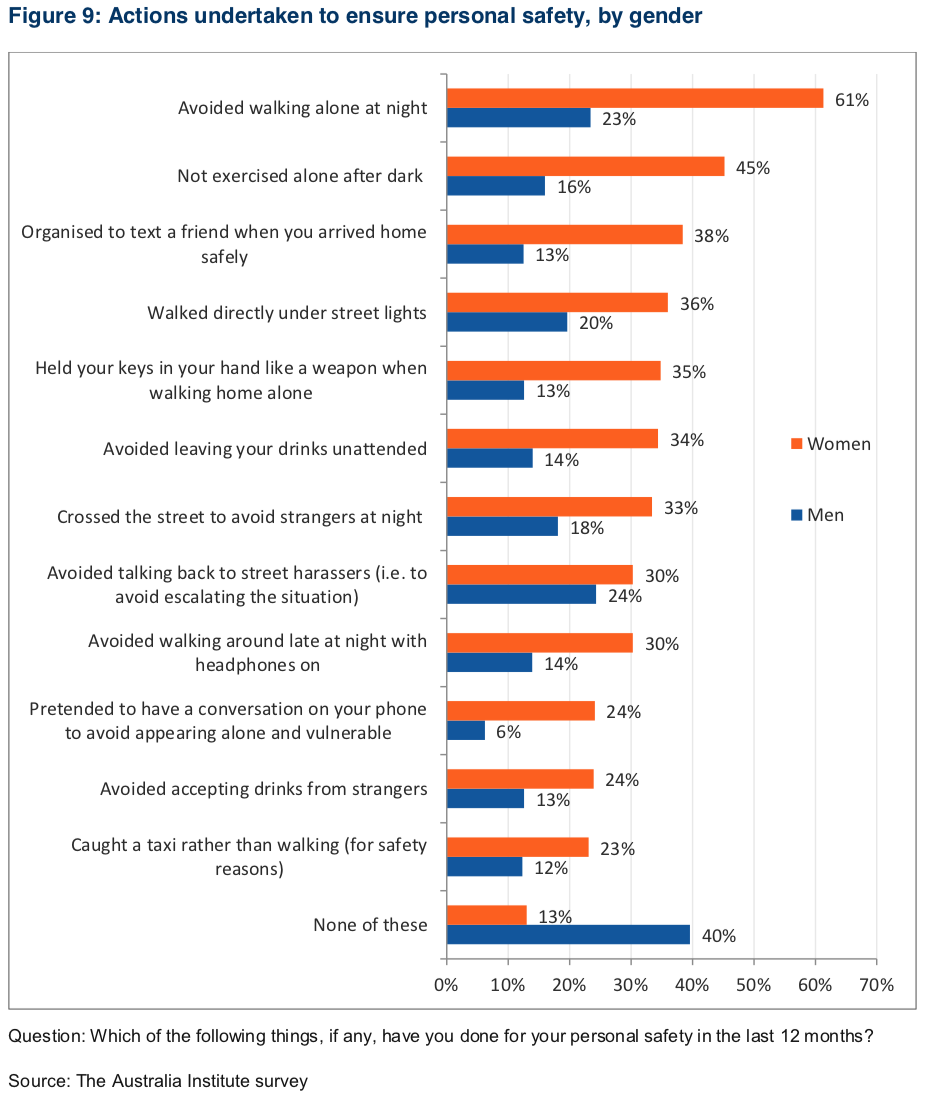

In order to avoid harassment, 61 per cent of women said they had changed their behaviour; for instance, they no longer walked alone at night.

Street harassment reduces a person to a single body part and objectifies them, explains Associate Professor Lisa Wynn, who heads the Anthropology Department at Sydney’s Macquarie University.

“Street harassment is harassment dressed up as a compliment,” says Wynn.

“If somebody’s calling out to you in the street in a way that is confronting, that’s not a compliment. That’s a form of harassment.”

So why do perpetrators engage in this behaviour? According to Wynn, they – usually men – see it as a way to connect with other men: something known as “male homo-social bonding”.

“It’s saying, ‘Look, this woman is not on our level, she’s a whole different category of being – she’s someone we can harass and get away with it.'”

While street harassment might be regarded by some as a trivial issue, it can have damaging and lasting effects on those who experience it.

Federal Greens Senator Larissa Waters has called for public harassment of women to be criminalised in Australia.

“It starts with catcalling, and if that’s not discouraged … those cultural norms get reinforced, and the mentality leads to gender inequality, objectification of women and violence,” she told 10 daily last year.

Last year, a Chicago man was charged with strangling a 19-year-old student to death because she ignored his catcalling advances.

The legal landscape

Around the world, policy-makers and law enforcement authorities are starting to take the issue of street harassment more seriously.

France, Belgium, Portugal and New Zealand are among countries that have specifically outlawed street harassment, while some cities, such as Amsterdam in the Netherlands, have taken similar steps.

Catcalling on streets and public transport in France can result in an on-the-spot fine of up to €750 ($1270).

In Australia, it is illegal to use “threatening, abusive or offensive language” in a public place – but that offence does not necessarily cover behaviour such as catcalling or wolf-whistling.

The penalties in NSW are relatively light, with a maximum $660 fine or 100 hours of community service.

Even reporting the problem can be challenging. If a group of men yell a sexually demeaning comment at a woman as they pass her in a speeding car, she probably won’t even get a chance to note the licence plate.

In the US, the group Stop Street Harassment operates a national hotline. In the UK, various bodies such as the British Transport Police have dedicated numbers for reporting harassment.

How big a problem is street harassment?

Hatch Macleay conducted an online survey on this issue. We present the results below, as well as some testimony from respondents.

Sarah*, 19, remembers being catcalled most days as she walked to school.

It upset her so much that she began walking to school in regular clothes and changing into her uniform when she arrived. This meant she had to leave home half an hour earlier.

Ari, 24, witnessed street harassment of other students on his way home from university.

“I didn’t intervene because I didn’t feel like I had the skills required to do anything to stop it. I actually regret not saying anything.”

Collective action

While they wait for the law and other mechanisms to catch up, women are taking matters into their own hands.

Initiatives such as Catcalls of NYC and Catcalls of London use public chalk art to raise awareness. They solicit stories of street harassment, chalk out the offending comments on pavements in the locations where they occurred, and post the images on social media.

They use the hashtag #stopstreetharassment.

Annie and Ari both told of wishing they had spoken out in response to the street harassment they experienced or witnessed.

Many people believe that if witnesses – ordinary members of the public – were to respond or intervene, street harassment would be significantly reduced.

One organisation, Hollaback!, is showing the way forward.

The award-winning group, which grew out of a conversation in New York in 2005 between seven young people, including its now executive director, Emily May, has become a global leader in the fight to stamp out street harassment.

It conducts training on how to intervene safely in such situations, and has developed a free safety app.

Hollaback! has formulated a “5 Ds” method, based on its surveys conducted with Cornell University in the US, which bystanders can use to make a difference: Distract, Delegate, Document, Delay and Direct.

The group’s research, published this year, shows that only 11 per cent of people take a stand against street harassment, while 81 per cent of victims say they wish someone had intervened.

Lisa Wynn, too, urges bystanders to speak up.

“If you see something, say something. Let people know that you don’t tolerate that.”

That sentiment is echoed by one anonymous target of harassment, who says: “I think we should stand strong together and not be afraid to speak out, even if it means creating a scene.”

Rosie’s story

One block down, one to go. Rosie*, 24, kept her head down, focused on reaching the spot where her ride service had arranged to pick her up. She had a fair distance to walk, because of a number of no-stopping zones.

Suddenly, she became aware of two men walking alongside her. “Hey, gorgeous, smile for me!” one of the men demanded.

“I was petrified, so I sped up and kept walking,” she says.

Since that incident, Rosie chooses to take back streets when walking alone at night, believing them safer. She says:

“I wish there were more places for rides to pick up people so I wouldn’t have to walk so far.”

Changing the environment

Rosie’s story demonstrates how the physical layout of a city can reduce street harassment. Elements such as better lighting, and fewer no-stopping zones, can play a significant part.

Zoë Condliffe, founder of She’s A Crowd, an Australian group advocating against gender-based violence and inequality, believes cities should follow a “universal design”.

“If you think about changing a space to suit the person who’s most challenged to access that space, then you’re designing it for everyone,” says Condliffe.

“They [city planners] apply this to disabled people, but never to gender.”

What is the solution?

Change needs to happen in both directions, with easier ways to report street harassment, and improved policies such as changes to city layouts.

Policy-makers in Australia should implement smart city designs and introduce measures to reduce harassment. These could include a reporting hotline and a public information campaign based on the 5Ds..

Every one of us should speak up if we witness harassment, remembering that, instead of just being a bystander, every one of us can be a hero.

What would YOU do if you witnessed street harassment?

*Names have been changed

For support, contact 1800 RESPECT or Crime Stoppers 1800 333 000