George Sternfeld comes through the door with the energy of a man half his age, waves and then walks straight past me. “Let me say ‘hi’ to my friends first,” he calls, loud enough that I can hear him across the café. The proprietor and the waiter greet the 81-year-old like a long-lost friend, bumping elbows over the counter.

“I’m meeting this young journalist over there,” George explains, pointing to my table. “Oh, so you’re the mysterious date she’s been waiting for,” laughs the owner and, without asking, serves him a long black with hot milk.

Lots of different accents can be heard here. George is Polish, while the café, A Man and His Monkey, in Sydney’s eastern suburbs, is run by a German and an Israeli.

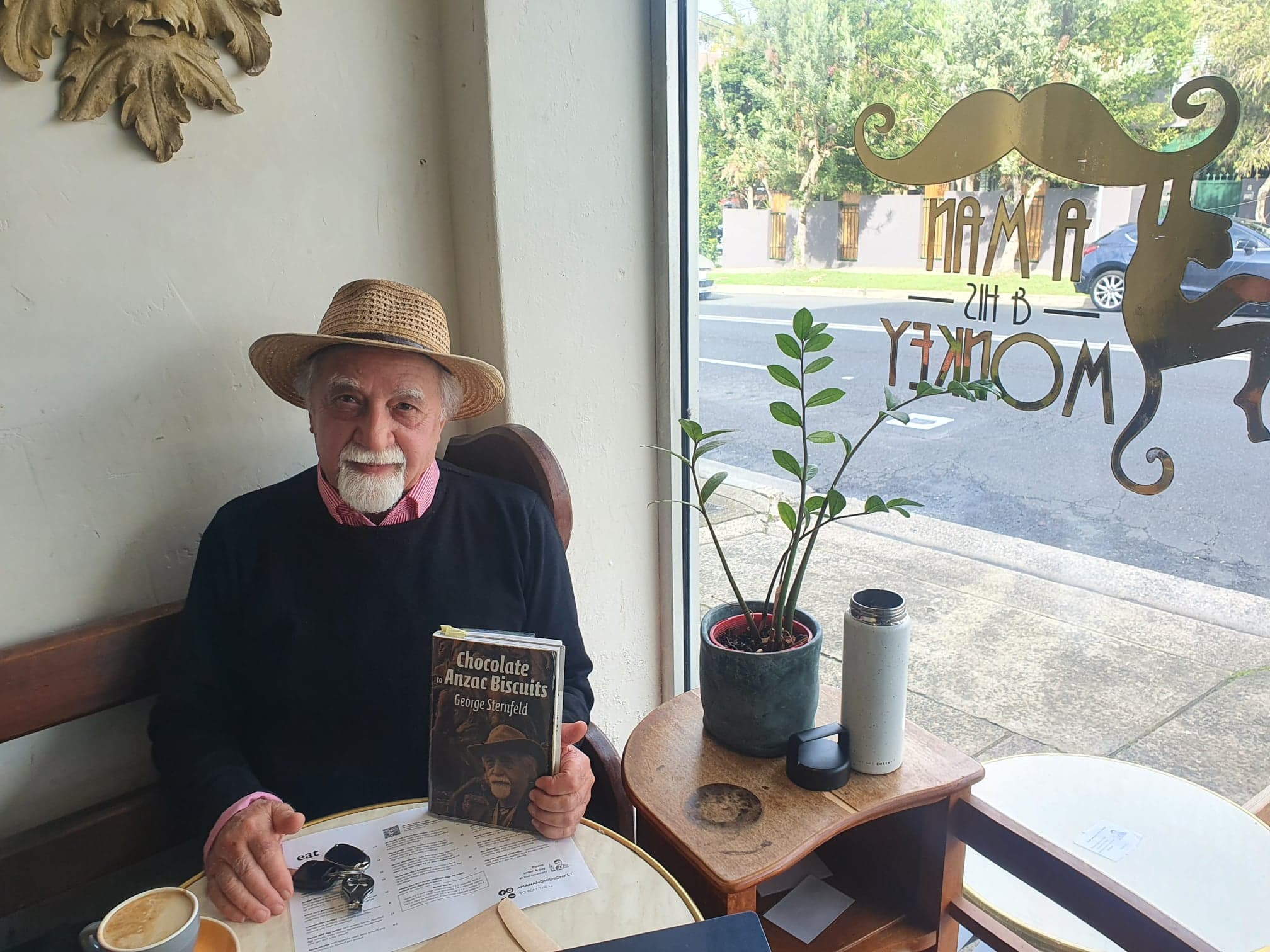

George, dressed in an elegant jumper, white sneakers and an Australian-made straw hat, makes his way through the throng. “Now, what do you want to eat? You must try the charred cauliflower!” The café is like a home from home for him, he explains. He and his Jewish friends used to meet here all the time. Of course, that was before coronavirus.

It’s not the first time George has been forced into isolation. His family fled Poland in 1939, and saw out the Second World War in a remote Siberian village. I ask him if recent months have brought back any traumatic childhood memories.

George takes his time to reply. After a first sip of his long black, he lowers his cup, and his voice. “Yes, isolation occasionally reminds me of the war. Though, I was only a child – I didn’t know any different. In retrospect, I can identify how it affected me mentally.

“Often I wake up at night because I had a dream from the past.”

Tight underneath his arm, George holds his book. It’s his life story, his journey as a Holocaust survivor. Chocolate to Anzac Biscuits, it’s called. Slowly, George starts telling the story he has told countless times before.

George Sternfeld was born in February 1939, in the middle of Warsaw’s Jewish ghetto. Just seven months later, war broke out across Europe. Recognising that being Jews in Poland would mean an inescapable death sentence, George’s parents decided to flee.

First, they had to figure out a way to cross the border. A river marked the frontier. By night, they embarked in a small boat across the icy water. Holding her six-month-old son, George’s mother knew a single cry would get them all shot.

George points to the book title. “My mother was a smart woman. Her pockets were filled with sweets. While our boat crossed the border, she kept feeding me with chocolate. All the way to Russia I kept still.”

The Sternfelds found a temporary home in the Siberian village, sheltered by mountain ranges, George’s childhood was shaped by hunger and temperatures of 50C below zero.

There was also the very early sense of not-belonging. “I grew up in a vacuum,” George remembers. “I never experienced uncles, aunties or grandparents. We didn’t speak any Russian, so I had to become fond of my own company.”

As soon as the war ended in 1945, the Sternfelds returned to Poland. Back home, nothing was left. They were the only surviving family members. All their relatives had been deported and killed, some in Auschwitz’s gas chambers.

Finally able to understand other children, George found he was still different. Now, his language was not the issue, but his name. Poland in the immediate post-war period was deeply anti-Semitic. He says:

“I couldn’t cross the street because kids were waiting to beat me up. Simply because I was Jewish.”

George became depressed and decided: “I had to learn how to defend myself.”

The 11-year-old told his parents he wanted to start boxing classes. By the end of the year, George was the school boxing champ. “Finally, the kids left me alone.” But he didn’t seek only physical strength. “I dedicated myself to maths and science.”

It turned out that Jew-hating wasn’t a phase that children grew out of. During the 1960s, anti-Semitism spread through Communist Eastern Europe. George’s father decided, once again, it was time to leave.

This time the Sternfelds chose a warmer destination. When George was 21, they set off by boat again, headed for a new life in Australia.

The German waiter serves us a colourful Middle Eastern mixed plate. As he splits avocado, yoghurt and bread onto our two plates, George’s voice quickens. “This is what I love about Sydney,” he says.

“You can have anything from any part of the world. It’s a delight to share all these different cultures here.”

George pulls out his smartphone. “Are you on Facebook?” he asks. Email and WhatsApp both work for him too. He swipes through photos of his own paintings, which he completed in isolation.

That’s how he got through Sydney’s lockdown: chatting with friends and family, listening to music on YouTube, and painting. And also, “I just finished my second book. This time it’s a book for children. It’s a story about the journeys of three different survivors.”

“You’re not eating,” George notices. “Eat, eat!” Appreciation of food is another Siberian war lesson. While my leftover bread gets wrapped up in a takeaway box, George puts his book back on the table.

The Sternfelds’ first port of call in Sydney was the “Chip Chip” – a migrant hostel where they lived for a year. “I didn’t speak a word of English. To support my family, I started working at a petrol station.”

A black and white photo in his book shows George in a dressing gown outside the family’s first house, in Greenwich, on the North Shore. George smiles and points to the book title again. This is where the Anzac biscuits come in.

“It was our first morning in Greenwich when our neighbour walked across the street, knocked on our door and offered us a package of Anzac biscuits.

“He didn’t care about my name; he didn’t care where I was from or what language I spoke. That’s when I knew I had arrived.”

George pursued his keen interest in maths and science, studying at RMIT University in Melbourne. After graduating, he was hired by a chemical research business as a polymer (a type of natural material or plastic) technologist – and stayed with the same company his whole working life.

He is now, he proudly finishes his story, the father of two sons and a grandfather of five.

“Now, would you like to meet my wife?” George asks as we’re leaving the café. “However, I must warn you, I’m a terrible driver.”

He’s not, it turns out. “Excellent parking,” I comment as George reverses up his steep driveway.

“Well, I’ve had 46 years of practice. That’s how long Liz and I have been living here. I bought it [this unit] right after our marriage. We have never moved.”

Liz, an energetic Australian-born woman, welcomes us and tells George to serve some tea and cookies. Their walls are covered in colourful oil paintings, mostly portraits and sunsets.

“Since we can’t go to any concerts or galleries, George started creating himself,” Liz says.

George, who serves up black tea with lemon and a plate of biscuits, is missing visiting Darlinghurst’s Jewish Museum. It’s the place where he usually shares his story with high school students.

He considers it a privilege to engage with young people, online and offline. He’s constantly writing letters to students, sharing his life stories and lessons. As George explains:

“I want them to remember, there is only one race in this world. And that’s the human race.

“What we see around us is a beautiful, colourful mosaic from different races, places and cultures. It’s the richness of humanity.”

Sliding two dark chocolate TimTams onto my plate, he adds: “There is no reason why we cannot share this beautiful world. This is what I want the younger generation to take away from talking to me.”