“Shoot them dead,” was Filipino President Rodrigo Duterte’s kill order for those that violate lockdown laws.

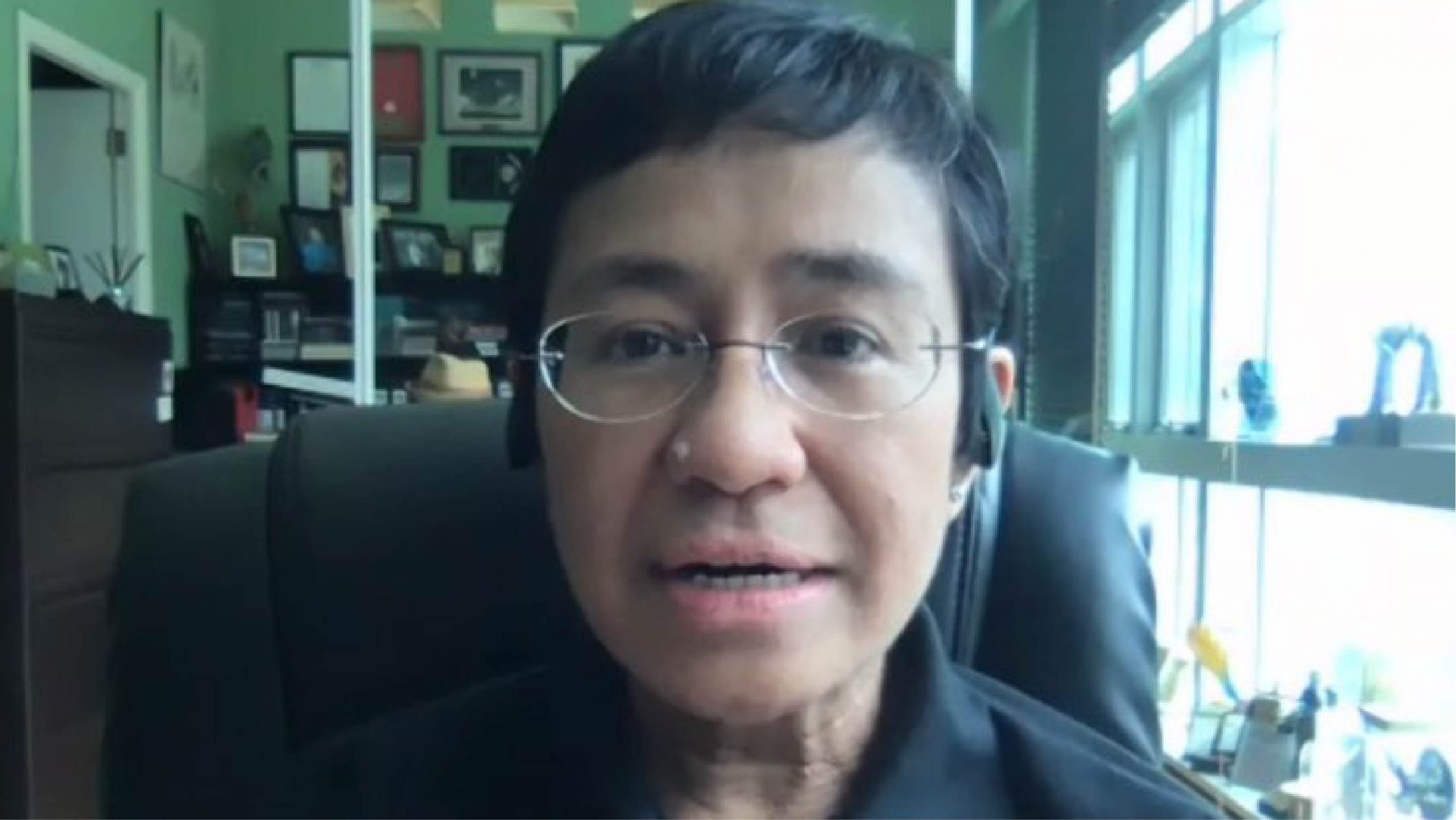

Just over a year after her arrest, Rappler CEO Maria Ressa sits in front of her computer, outside the confines of prison, but locked inside her mint-walled house.

Like the majority of the world, she is in quarantine, Zoom-ing in with Macleay College students in Sydney and Melbourne.

For a workaholic like Ressa, the downside of working from home is that she is working all the time.

“I can be at this chair from 8am to midnight,” she said, sporting a black polo shirt with her company Rappler’s orange logo on her chest.

“I’ve always, from the beginning of my career, said, ‘no story is worth dying for’ – I still believe in that.”

Maria Ressa on the role of journalism

For young journalists confused on the role their industry plays in such unprecedented times, the CEO of Rappler’s special appearance assures press freedom hasn’t given up on its timeless battle.

“Our mission has always been to hold power to account,” she told students and lecturers.

Even as Ressa equates journalism as the bridge between government and the public, the novelty of SARS-CoV-2 is changing the fourth estate’s role.

“I’ve actually asked Rapplers to work from home because there are too many things that are ‘novel’ about this coronavirus,” she said, signalling quote marks with her fingers.

“I’ve always, from the beginning of my career, said, ‘no story is worth dying for’ – I still believe in that.”

Although Rappler’s journalists are safely working from home, Ressa still questions how to assess accountability journalism when the only source of information is the authority.

“Power doesn’t ever listen – power, it reacts.”

Following President Duterte’s first public announcement to declare a lockdown, Rappler’s editorial team agreed on an agenda: “tests on every front.”

“I started realising that we’re still relying too much on the government’s numbers without any check,” she said.

According to Ressa, the crucial question journalists today must ask is: “How do you check what power says?”

She adds: “Power doesn’t ever listen – power, it reacts.”

“It should force all of us to re-imagine the role of journalism today.”

Meanwhile, with multiple governments around the world, including Australia, supporting location tracking apps to curb coronavirus infection rates, mass surveillance has never been a bigger threat to democracy.

“I interviewed Edward Snowden and he was pointing out that this was precisely why he became a whistleblower,” she casually shared.

“He saw that mass surveillance was occurring at a massive scale in governments’ hands.”

With tech platforms and their capabilities amplified by the power of artificial intelligence (AI), these machines now know us more intimately than the closest people in our lives.

“The end goal of (artificial intelligence) is actually to modify our behaviour – behaviour modification.”

Maria Ressa on the negative impact of AI

Providing Facebook’s notorious AI as an example, Ressa says that these machines are sniping for our most vulnerable moments to manipulate our behaviour.

“The end goal of that is actually to modify our behaviour – behaviour modification,” she said.

The Philippines hosts over 70 million Facebook users that make-up almost 70 per cent of the entire population. For the past three years, Ressa has been struggling to figure out the role of Facebook within this digitised population.

“We should demand that these platforms give us ownership of our data because we’re the ones who put in our actions,” she suggests.

In a recent piece she wrote for Time, Ressa explored the immense powers handed to authoritarian leaders to deal with the outbreak.

While trying to figure out how people are to retain power, Ressa witnessed Facebook’s censorship of anti-government posts in Vietnam.

Vietnam’s experience hits Ressa close to home, as Facebook has continued to allow social media attacks and weaponisation of the law by the Filipino authorities.

“This is what I went through,” she said

“The same attacks on social media that were pummeled into the public designed to take down my credibility were the same cases that were filed by [the] government a year later.”

Unfortunately, she still hasn’t figured out how people, in nations that have conceded power to authorities, are to conserve democracy following the pandemic.

“I don’t know what the world is going to look like post-COVID.

No one knows what the world will look like, but Ressa left some generous advice for journalists that will venture out into the new post-COVID world.

“First is, imagine what journalism will become,” she said. “Our mission, the mission of journalism is far more critical today than it ever has been.”

To add to that, Ressa stresses the importance of people who are “going to run the business”.

Reminded of a good example, she smiled and shared a story of Rappler’s rock-like CFO Marie Fel Dalafu, who dreamt of being a journalist, once upon a time.

“The only reason she moved into finance was she came from a family that wasn’t well off,” she said.

“You must have the courage to challenge authority when all of the traditional support networks are too big.”

Maria Ressa’s final advice to journalism students and lecturers

To pursue her dream in a different manner, Dalafu identified a position that is present in every media organisation. Luckily for Ressa, Rappler was her eventual employer.

“We wouldn’t have survived [the] government’s attacks to bankrupt us if we didn’t have a woman like her as our CFO.”

Her second advice for young journalists: “Courage.”

“You must have the courage to challenge authority when all of the traditional support networks are too big,” she urged.

According to Ressa, the three biggest challenges that require courage and imagination to figure out are the pandemic, the battle for truth, and climate.

Rappler’s editorial agenda was set-up around the sustainable development goals of the UN.

“Which newsgroup does something that geeky?”

Full interview transcript:

Yohan: Everyone, thank you so much for joining us today. We have a very, very special guest for all of you. Maria Ressa, who does not need many introduction at all, but I’ll try anyways.

She is a symbol of press freedom and a model journalist that has already inspired future generations like myself. But what makes her most interesting to me, is her drive to continue to stay closely connected with the most relevant issues that threaten our industry today. And she’s remained consistent in setting a standard not just for what we do as journalists, but why we do them. So, guys, it’s my absolute pleasure and honour to introduce Maria Ressa to all of you.

Thank you so much for joining us, Maria. How are you doing today?

Maria: Very good. Yohan, that’s one of the best introductions I’ve really gotten. Thank you so much. Thanks for having me, and guys, thank you for setting aside time to spend the hour with me.

Yohan: It’s our pleasure. Are you in quarantine like everyone, Maria?

Maria: This is the end of week six for us, in Manila. Yeah.

Yohan: What have you been doing to keep yourself busy at home?

Maria: Oh, my God. So first, let me start with the silver linings. This is the most time I have ever spent in my apartment since I moved back to Manila in 2005. I’d never been here. I actually now can sleep, which is good. But the downside of working from home is you work all the time. I’m sure you guys all know this. If you don’t delineate, if you don’t do a stop sign, I can be at this chair from 8:00 a.m. to midnight, with maybe a small break. You know, my meals – I have breakfast here. So, that’s the tough part. But I think the other thing that powers me through all of this is, it’s such a weird, interesting, historic moment.

And just waking up to that every day, trying to figure out how are we going to evolve journalism? That’s the other part. It’s in our hands to create our future. It’s in your hands to create the future that we’re going to live in.

We’ve never really lived through anything like that. So that’s what keeps me going.

And I exercise! I make sure I try to get at least 20 minutes on the treadmill, even if it is like while reading a report. But it’s a good time, in a weird way, in a bad time.

Yohan: It’s great to hear that. I’ve actually been doing some jump ropes myself as well. I’m very glad you mentioned what we’re going through right now. It’s very unusual, as you said.

But what’s most interesting to me is that I’m getting very confused about the media’s role in such a global pandemic like this one. Having said that, from an experienced journalist like yourself, what would the role of journalism be in a global pandemic like we’re experiencing today?

Maria: So, let’s start with the traditional one-sentence description of “what do journalists do?” Our mission has always been to hold power to account. We were, in the old days before social media, the connective tissue between the people we elect and the people that elected them, the public.

In a time of pandemic, that actually changes because there are two dynamics at play. In order to deal with the virus (and it is global in nature), we give greater powers to our leaders. That’s a given. Extraordinary measures for extraordinary times.

And then, the journalists themselves. While we have passes (I mean, I just came from outside), while journalists can go out even though the quarantine is there, I’ve actually asked Rapplers to work from home because there are too many things that are “novel” about this coronavirus. It’s too new. I’ve always, from the beginning of my career, said, “no story is worth dying for” – I still believe in that. And that changes in the time of a pandemic.

And then the last really important part that we assess every day is what does accountability journalism mean when all the information is coming from the state?

When you are alone at home together, the way we are. What does that mean? So some of our answers:

When President Duterte had his first public announcement in the evening on March 12th, declaring a lockdown, and the lockdown was actually going to start on the Ides of March on the 15th.

So there were two days where people fled Manila. So what I’m worried about is just like northern Italy, that spread is what would have spread outside of Metro Manila.

So on that day, once we saw he was declaring a lockdown for a month, the founders of Rappler got together and we said, “What are we going to do editorially?” You have to set the editorial agenda. What is that about?

And at that time period, what we decided the agenda was, that we were going to be moving ahead of government. And the agenda of Rappler at that point was: “tests on every front.”

How many tests are being done? Why aren’t more being done? We crunched the data in the next day and we found out that in the first week of March, like the first week of the lockdown, only 12 Filipinos for every million Filipinos, there are 100 million Filipinos, only 12 for every million had been tested. And then we declared a lockdown. What was the basis of declaring a lockdown? How do we know when to lift? So that powered our editorial agenda for a while.

Two weeks ago, I started realising that we’re still relying too much on the government’s numbers without any check. And I guess that’s the question. That’s the crucial question you always have to answer. How do you check what power says? Because power doesn’t ever listen. You know, power it reacts. Right?

So what we thought then, was, I began to look at what everyone else around the world was doing. And in New York, Cuomo was looking at the number of people being admitted to hospital for Covid-19, and that became his leading indicator, because if not enough tests are being done, what can you monitor that will give you an idea of — sorry, I’m going to get rid of our popups.

We have so many of them. What can be the leading indicator so that you can then hold power to account? Right? So that’s what we’re searching for right now because I thought about that. But there’s no way that we can actually get the data.

So we’re working with other tech people, other data people. And I guess that’s the other part, right? Journalists role in convening, journalists role in trying to empower communities. Not just to ask the right questions, but to find the answers. And then I guess this is the last part of my answer to you.

I think the world is changing a lot. And in four years ago, when the government began attacking Rappler, I moved from being a very traditional journalist.

Like, I was a broadcast journalist and I moved from thinking like a broadcast journalist in kind of this objective journalism way that never really existed, to all of a sudden when I got arrested, I was unshackled and I was faced with the question of, do I speak as Maria Ressa, the person who’s right, my government violated or do I speak as Maria Ressa, the journalist who doesn’t comment on things like this?

What I decided to do, you know. I decided that I was getting first-hand knowledge of how power behaves and I could see that they were abusing the powers they were given.

So I rang the alarm bells. And that’s kind of the fusion of Rappler. I still try to take myself away from Rappler. But, you know, Rappler in 2018 was charged and investigated for eleven cases.

Seven of them stemming from one incident with the same set of facts. So that’s forum shopping by any imagination. These cases should have never have been to court, but they did.

So I had to rethink in an upside-down world. I say this, you know, I felt like I was Alice in Wonderland and I fell in the rabbit hole and the Mad Hatter was in charge.

So in that world, how do I behave? How do I keep the values I believe in? How does Rappler behave? Does it behave separately from me? These were all questions we had to challenge.

So that’s a long-winded answer to your question. But the right answer to that is that this creative destruction we are living through is global in nature. It should force all of us to imagine the role, re-imagine the role of journalism today.

Look at the needs of our communities and then see how we evolve to fulfil those needs. And at the same time, maintain the standards and ethics we’ve always had.

I think the strategic mission, the goals and the mission of journalism hasn’t changed. It’s just the tactics to evolve with the times.

Yohan: When you say we evolved with the times, I think we can very clearly explore how the industry has evolved through exploring your career because we’ve seen technology evolve with your career as well. As we talk right now through technology as well, another issue arises and that is privacy.

So how do we balance technology and privacy in times like these where we have to rely so heavily on devices and technology to get us going?

Maria: So let me pull it back up to government and power and mass surveillance. Two nights ago, I interviewed Edward Snowden and he was pointing out that this was precisely why he became a whistleblower, because he saw that mass surveillance was occurring at a massive scale in governments’ hands.

Then let me add to you, I don’t know if you’ve read Shushana Zubov’s book “Surveillance Capitalism,” which is aside from government, you have the tech platforms whose data gathering capabilities, now powered with artificial intelligence, actually know each of us far more intimately than our partners, our family, our best friends.

The artificial intelligence that is in Facebook is looking for that moment when we are most vulnerable to a message they are paid to give us – the advertising.

And the end goal of that is actually to modify our behaviour – behaviour modification. So your question is about data privacy. I guess part of it is the concepts we have of it are outdated.

It’s like trying to close the barn door after the horse has already left, or the cow – whatever the metaphor is.

So it’s a very, very different world today. These companies and government already have our data. And the question is, how can we curtail that? So one of the things that I’ve had is, the opt-in is gone. You can’t opt-in or opt-out.

You walk outside the streets in Singapore, in Manila, and cameras will pick you up. They never asked for your permission, but governments have that right.

I don’t know what it’s like in Sydney or Melbourne, but they were part of the Five Eyes – you guys are part of the Five Eyes. And some of what Edward Snowden talked about was the actions of the Five Eyes. So I struggled maybe for the last three years to figure out what Facebook’s role is.

Facebook played at an ordinate. It was in a position to determine the public sphere in the Philippines. Facebook was our Internet. Every person on the internet in the Philippines, and that was like 70 some odd million, are on Facebook.

So when I looked at that and privacy issues, the idea that we came out with, and it’s not an original idea but it was something that we talked about, some states in the US are using this: that we should demand that these platforms give us ownership of our data because we’re the ones who put in our actions. And then the platform takes it and collectively it begins to be able to see trends and to make money off of us. And then they get pictures of us that, you know, they can predict what we’re going to do sometimes before we do it. That’s artificial intelligence.

Anyway, so what I’m saying is that, look, we can’t expect Facebook or YouTube or Twitter to act against its commercial interests. It’s never been that way.

And their commercial interests have rewarded them. When a government does a disinformation campaign on Facebook, or on YouTube, they get more revenues. So do they care much about it? Well, so far, no. In fact, when Mark Zuckerberg was at George Washington University, he essentially said it’s OK for politicians to lie. He said, well, it’s got to be a free space. Look, these platforms now determine what you get.

The distribution determines facts, so facts can now be lies or lies are turned into facts. And that’s part of the reason. Beginning in 2016, 2017, 2018, the entire world was caught in this battle for truth.

I still haven’t told you what the idea is. So I’ll focus. Sorry. It’s a broad question.

But what if the incentive for Facebook is that if they don’t protect the user, instead of blaming the user for getting attacked for the things they did for the lack of gate keeping they put in place? What if the user can opt to leave Facebook with all the data? Right? So if Facebook doesn’t protect me, I can go and just say “Facebook, I don’t like you,” and then transfer all of the data I built on Facebook to a new social media platform. Is it Space? There’s another new one that’s being created, I guess, it empowers the users instead of making the users the scapegoat instead of making it the user’s responsibility. We get control over something we created. That’s some states in the U.S. are actually pushing that. But that’s an easy way for trying to control platforms.

Trying to control governments and hold in check the immense power they have, I think that’s a collective civic engagement problem that is redefining what democracy is today. And you cannot have civic engagement if we cannot agree on the facts. And that’s what we’re seeing with disinformation. It pounds lies into your heads as facts.

That’s what we’re seeing with the IRA, with a GRU with Iranian disinformation, with Filipino disinformation. So I try to figure out the hierarchy and get to everything goes right back to that same adage we’ve always known: information is power.

Whoever has the information wins. Joseph Stiglitz got his Nobel Prize in economics in 2001 for how markets were skewed by information asymmetry.

That’s right. Exactly where we are today, except in this day and age, the wrong information, information can kill. Information can cut down our constitutional right. So that’s the battle we’re in.

Yohan: It’s very interesting that you mention Facebook in so much detail because Rappler originally started as the Facebook page, back then known as MovePh. And you’ve also been very vocal about how social media today is being weaponised to target journalists like yourself and us. So, can you share with us some of your experiences that led you to make these kinds of statements, and why we should be worried about your experience?

Maria: I think it’s also now your experiences. You know, we were only first in 2016 because, if you remember, Rodrigo Duterte was elected in May 2016, and then a month later, Brexit happened, and then Trump was elected later, and then the Catalonia elections in Spain.

I mean, it’s like the dominoes started falling in 2016 for practices that were originated as early as 2014 in the Ukraine.

So, why should we? The data is there now. The facts are clear. The FBI, the Mueller Report, lays out how Russian disinformation affected the 2016 elections.

There have been books written about it. I’m not that familiar with Australia. I am very familiar with the Philippines. We mapped our information ecosystem and we have a database we call the Shark Tank, where we have chronicled wave upon wave upon wave of new disinformation that works.

So this is like an arms race, when the platform detects it, and they take it down, something else takes its place and they keep learning. It is literally an arms race. The silver lining in the pandemic is that Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter are actually doing things that they had refused to do to protect democracy, but because we are all in the same boat, whether you’re Facebook or you’re Google or you’re Twitter, they are working from home. We can all catch this coronavirus, the SARS-CoV-2 virus and get Covid-19.

So they are now doing unprecedented things and I think we should keep track of that. They’ve taken down tweets and posts by Giuliani by Bolosonaro who denies that you should actually have social distancing.

They’ve taken down networks of Duterte propagandists on Twitter, and Twitter actually gave a statement when they were asked by The Washington Post, this is very recently.

So, again, I look for the silver lining. I think, maybe, I hope, that the people who are running these very powerful gatekeepers now realise the impact of a lie.

Yohan: When we talk about the impact of a lie like you just mentioned, do you worry at all, that some of the authorities, some governments could weaponise the global pandemic to challenge democracy today?

Maria: It’s happening. That’s actually a piece I wrote for Time, where if you look all around the world, leaders all around the world, look, I have no problem giving Angela Merkel greater powers because she’s a scientist, she understands it, she’s making the right decisions, and you can see [it]. But again, what I wrote for Time was, I looked all around the world that all these countries where these extraordinary powers to deal with the virus are being handled by authoritarian style leaders, and I look at the Philippines. Instead of actually strengthening our public health care system at the beginning, the Executive asked for emergency extraordinary emergency powers and he got it within 24 hours.

The only thing that we were able to do was to put a three-month time limit on it. We’re all too willing to give up these things because we know what has to happen.

But the next question is, you know, what do you do with an Orban who has unlimited powers forever? How are Hungarians going to get that back? How are journalists going to deal with that?

The amount of laws that have been passed, you can understand it. In your mind, you know why, right? Because we know the impact of a lie.

But when a government like Vietnam, for example, this is something alarming to me, and I’m trying to figure out whether I want to write it because it may give the Philippine government ideas, yesterday, an exclusive article by Reuters said that Vietnam chortled the pipeline of Facebook.

So they slowed down to traffic on Facebook in Vietnam and they wouldn’t open it up unless Facebook took down anti-government post and Facebook agreed to do it.

This is the second time they’ve done that. They did it in Cambodia. They did it in Vietnam. You could argue if you were Facebook, that, ‘Well, they’re authoritarian. They’re military dictatorships anyway. Those governments are in power. Why would we change?’

But then what happens to the Philippines, where they haven’t taken action and they’ve allowed the kinds of exponential attacks that tear down reputation and then allow the weaponisation of the law?

This is what I went through, right? The same attacks on social media that were pummeled into the public designed to take down my credibility were the same cases that were filed by government a year later.

So it was like social media is the fertiliser changing public opinion, shifting public opinion for a measure that the government wants to take? What do you do with that?

How do you deal with this authoritarian style takeover of power? I think the jury is still out. You have to tell me what it’s like in Australia right now.

But in the Philippines, I’ll tell you, we, in that 24 hours, Congress went into emergency session in the wee hours of the morning at like two in the morning, they stuck in a clause that essentially allows the government to jail, somebody who does fake news for a month, for two months, I think, and then fine them twenty thousand dollars, US dollars – a million pesos. That was just snuck in.

But one of the things that the civic groups pushed in was that there’d be a three-month time limit, that it be re-evaluated. I don’t know what the world is going to look like post-Covid.

But I think that’s one of the things that we should be trying to look at as journalists. And what are the leading indicators we should be looking at? And, you know, I look at that not only as a journalist, but because I run a business, I’m the CEO of this company.

And that means I needed to look when the lockdown happened. Not only did we look at our editorial policy, but I then looked at what are our H.R. policies. What about our accounts receivable if we’re in lockdown for a month? That means we can’t collect cash. How long is our cash flow going to last? What are we going to have to do? What emergency measures should we put in place? And here’s the last part of that, the economy. People have always said that there are two curves. You have to measure the flattening the curve of Covid-19.

And then at the same time, the more time that takes, the longer the recession curve, the longer your country will feel the economic impact of that. So that’s one of the things we’re trying to figure out now.

Yohan: In your answer just now, you’ve mentioned some countries such as Cambodia, Vietnam, and these are countries that are currently being influenced by what we’re calling the Chinese media model.

And I’m sure you’ve read the recent RSF Press Freedom Index, which was released just a few days ago, and what’s really interesting to me is that with this model going around, we call it censorship but in the Chinese Party, they call it supervision in the name of national security.

So where do we draw the line in terms of handling information? What can we call supervision? And what can we call national security?

Maria: First, we have to be very, very careful what we know and formalise. The kinds of surveillance systems that China has made the norm in China, and that it is bringing to its allied nations, including the Philippines, violates the Philippine constitution.

This is not Big Brother trying to protect us. Yes, maybe that’s a byproduct. But they tend to use it for power. So one of the things you can look at is as China is doing this, they are also expanding in the South China Sea – what the Philippines calls the West Philippine Sea. They’ve been building, while they’re trying – so first they had to rehabilitate their image, and you’ve seen all the conspiracy theories and they’ve taken on the Russian disinformation style of attack on social media. And like Russia, they’re using traditional media as well.

So there’s the rehabilitation of the image of China. There’s well, you know, China now is going to help all of these countries, but they send defective masks to Italy.

They send defective masks to the Philippines. And then our own Department of Health says, “No, that’s not that wasn’t from China. That was from a private company,” but never tell us what the private company is.

So power — I think two things are happening and I’ll talk from the Philippine experience. The first is the incompetence of power. When you have incompetence and arrogance combined, it is a really, really difficult to hold them to account, and it makes me very worried about what will happen to the Philippines. But that’s kind of what we’re dealing with.

We had a town mayor from Davao City become the head of the nation, and he has appointed people from Davao City who had no real national exposure.

So they are now dealing with these extraordinary times instead of, for example, utilising a system that government already had to deal with disasters, The National Disaster Risk Reduction Council, they created something completely new with no workflows. Sorry. I won’t dive in too many details.

But again, we want competent leadership that in and of itself holds itself to account to the spirit of the constitution. At no way, in no way, shape or form does China do that. China takes power, China retains power, and it is global in its appetite for power. And I think that’s one of the things. Now, I don’t want to sound like a China hater or a China rumour monger.

This is where journalists have to get to the facts. I think that I still worry. China has just last week, or is it this week, they increased by like more than 50 per cent, the death toll in Wuhan.

I think it’s Missouri or there’s a U.S. state that filed a case against China because they kept quiet about the pandemic.

They filed the case for damages. This was, I think, yesterday or the day before.

So I guess let me end with just this one thing. How do we determine what good leadership is? No matter what political system you have, let’s say you don’t have a democracy.

I still think in the end it comes down to three things. And whatever that government is, should be holding itself to account.

Transparency, accountability and consistency. This pandemic is showing all of that. It shows you the strength of the public health care system of the country.

It shows you the quality of the crisis leadership and then the amount of trust that is there, how that leadership communicates with its people, whether you are like Vietnam, which is very heavy-handed.

Or whether you’re like the Philippines, which is trying to woo. They don’t want to call themselves a dictatorship right now, and they’re not.

We’re in transition. But those three things, transparent, accountable, consistent, because no person, I would think, even when you if you live under Bolsonaro in [Brazil], you want to know what the world looks like, you want to know what to avoid, you want to know that your government is coordinating to get masks to the right people, to get the PPEs, the right people.

Yohan: Thanks so much for that, Maria. We’re almost running out of time and other students would love to ask you some questions as well, even though I’d like to continue to keep going.

But before I do turn you over to other students, may I ask you a final question, and that is what is your final advice for journalism students like ourselves in such unusual times like these?

Maria: So the first is to imagine what journalism will become. So the foundation is that journalism has never been as necessary as it is today.

Our mission, the mission of journalism is far more critical today than it ever has been. But the institutions of journalism, news organisations are under threat and they’re under threat business-wise, the advertising model is dead, we’re under threat by the platforms, which is not just taking the advertising, this is before coronavirus, they took the advertising, but they’re also the platforms where our credibility is attacked, and are the ones used to manipulate public opinion, whether it’s a company or a nation. So that’s the foundation.

But then on top of that, as you come into journalism, and this is a challenge for teachers, for the teachers who are teaching it. You have to imagine how these foundations distil what the mission is, what the reasons for being are is on debt.

And then you have to overlay it onto the reality we live in today. You, like us, the people who are practising it right now, you have the ability to practice it right now, right?

We’re imagining what journalism is going to become. I think that is very empowering. At the same time, you know, not only need journalists, you need people who are going to run the businesses.

So, you know, like, I’ll tell you the funny thing. Like, our CFO is so incredible. I kept wondering when all the attacks came against Rappler.

She was just such a rock. And then I realised it was because she wanted to be a journalist. And then the only reason she moved into finance was she came from a family that wasn’t well off.

And she felt that they couldn’t afford the top school. She always knew she wanted to do journalism. So she went and took accounting. She tried to figure out, “what does every newsgroup need?” So she majored in accounting.

She told us in one of our of our company meetings. She said, now she’s very proud that she’s working with the – she calls us the best journalists. We wouldn’t have survived government’s attacks to bankrupt us if we didn’t have a woman like her as our CFO, because they tried to scare everybody. And so I guess that’s the last part.

What do you need? Courage. Courage. That is the quality that journalists will need today.

Because you must have the courage to challenge authority when all of the traditional support networks are too big.

You must have the courage to imagine the world as it should be, not, leave behind what it is. Imagine what it should be, and then find the steps to make it that way.

And then evolve. The business of journalism is evolving in front of our eyes and I have a feeling that it is going to work very closely with these platforms I keep attacking.

They’ve got the money. But we cannot cave-in. They don’t have the same principles journalists do. Long-winded answer, so I’ll shut up.

I think that it’s a very exciting time. You can be limited only by your imagination. I use that word a lot because that’s an important thing.

The three biggest challenges that we face today require imagination to figure out. That’s the pandemic, the battle for truth, which is what happened to us. And then the very, very first battle yesterday was Earth Day, the 50th anniversary of Earth’s Day – climate.

The Philippines is one of the most disaster-prone countries around the world. And when we started Rappler, climate was our first goal – editorial agenda.

In fact, we set up our editorial agenda around the sustainable development goals of the U.N.

Which newsgroup does something that geeky? But you could do it. You just have to find really good ways of telling stories.